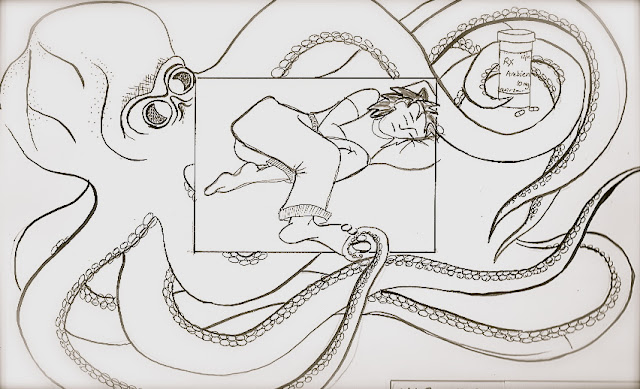

Study (2012) Miranda Field

My friend, K, took me to see her house, an old, once-grand, four story building in Washington Heights, in her husband's family for several generations. Since her mother-in-law's death last winter K has been sole effectual caretaker. Her husband has been unwilling, or unable, to perform any of the small gestures required to ward off decay in a building. Not only that, but he's been filling the untenanted upper rooms with junk, to the point where the doors can barely be opened. It's an utterly haunted house.

K's husband slept on a pallet on the floor next to his mother's bed all the many, many months of her final decline. After she died, he stayed there a while, on his pallet, on the floor. You have to get him out of there, a friend warned her. This friend told her his own brother had done the same thing-- stayed in the house they grew up in, and in which their mother eventually died. He had stayed, he'd turned a little strange, and it didn't seem he'd ever leave now.

The house is big, old-- high ceilings, massive bannisters, tall, wavy-glassed windows, softly undulating, mildewed plaster walls: it's a Manhattan developer's dream, but only because of the space it takes up-- the plot of pure gold real estate. I imagine K wishes she could somehow uproot it, lift it away from the place on the map that gives it its magical dollar value. If she could put it in a field, in the middle of nowhere--. Oh, maybe not. The loneliness of the house, stuck on this island of a million-and-a-half souls, stranded on a major drug block, filled with all its different shades of eerie late-afternoon light, is palpable. It's still in the family, and the family isn't letting go. But it's an otherworldly family, that clings to this structure on this property worth god knows how much, and lives poor.

The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which, at least in my sketchy Western understanding of it, sums up the mood that engulfed us as we stood just inside the front door of K's house. An esthetic response woken up by the acute awareness that nothing lasts, that everything-- including yourself-- is subject to disappearance, decay. We both go silent a minute, then K unlocks another, inner door.

|

| Ingress (2012) |

Clearly K's house overwhelms her. It has suffered decades of neglect. "Neglect" is what we call it when something's left unprotected from the effects of time, and starts to show signs that it won't last, that it's subject to disappearance, decay. It's neglect, that is, if someone who should have didn't raise a hand to resist time's habit of eating away at things. K used to think she and her husband would move into the middle two floors and have a life. But their marriage, since this house became theirs, has become a grey area.

Growing up in a haunted house my sisters and I were ever hopeful that the adults-- moody, self-absorbed, busy with their art and their books and their troubles-- might step in, stop everything from falling apart, getting lost, becoming non-functional. Now that we are the adults-- hah-- moody, troubled, out of our depths, what are our children are waiting for us to do?

Things break down in time. Sometimes entropy is unconsciously assisted. Sometimes things are intentionally smashed. Windowpanes are replaced with corrugated cardboard. My father had a colleague at the art school where he taught whose own father, when another and another crack would appear in a wall, would drag himself up out of his chair with a sigh, and tack another and another shed snakeskin over the crack. The chill breath of the damp, moldy basement of K's house might have come directly from my own childhood across the Atlantic.

*

|

His Grandmother's Furniture (2012) Miranda Field

|

So many of my closest friends go through life dragging their haunted houses behind them. I've wondered about that. Maybe it's how I recognize these people when I meet them. But K, in standing on the top stair of her giant cracked and leaking house with all its junk and all its broken, beautiful, mottled treasures, she seems hitched to a particularly heavy weight. "For the last few years," she writes me, in an email, "I have felt like I am the old lady in the house alone."

|

Now and Then He Makes an Effort

|

*

"Knock-Knock," one of my favorite joke goes,

"Who's there?"

"Death"

"Death wh--."

*

Oh god (a memory, from nowhere) suddenly I remember there was a large suitcase in our cellar, into which one of our cats had crawled to give birth, unbeknown to us, just before we left for a 6-week vacation. When my mother locked everything up for the summer, she unknowingly separated the cat from her kittens. By the time we returned, the newborn litter was nothing but a mess of mummified pelts stuck to the case's lining. I was haunted by the suitcase in the basement for the rest of my childhood. It was a terrible scenario to imagine-- the frantic cat, the dying kittens-- but what made the impression so indelible for me was the fact that no one (as far as I know) ever got around to cleaning the terrible residue up.

*

My dear friend, C, says, over breakfast at our diner, over coffee mugs heavy as plumbing fixtures: "My blood is elegy." She's thinking it would be good for her to take a comedy improv class. I can't think of anyone less intended for a life in comedy. Unless it's K. But, actually, K was, back in the day, an actor, though I know no details of that phase of her life. One of those stunning women slated from the beginning to pay for her stunning younger self's genetic good fortune with her older self's debilitatingly anxious self doubt and self-denial, she never accepts even the tiniest edible thing I offer her. I've never been able to persuade K to eat at my table. After we've seen her house, we walk up Broadway to 165th, and wander into the Shabazz Center, to see if we can catch a glimpse of the Audubon Ballroom. The ballroom has been renovated-- sheet-rocked and track-lighted-- into a slick, soulless little conference room (no vaulted ceiling, no tangible residue of history), but a ghostly photo of Malcolm X is housed in a glass case on the section of the original wood floor where his body fell.

Somewhere in the apartment K lives in with her husband, son and daughter (a few blocks away from the house, in little Dominica) there's a box of old photos she rescued from one of her husband's tangles of unfaceable things. In it there's a photo of his parents-- K's mother-in-law, whose death was a long, slow sinking into physical and mental breakdown, is young, gorgeous, smiling her thousand-watt smile -- wearing her sassy but elegant dance dress, at the Audubon, ten years before Malcolm X's assassination.

|

Malcolm X

|

"Sometimes I feel so ungrateful," K says. We've returned to her building, I having had a sandwich, K a cup of tea, at a cafe next to Shabazz. We're standing in the back yard of her building, looking up at the walls, great cracks running down them, and electrical wires of all types and vintages draped like seriously ancient, knotted veins and arteries. This part of the house died long ago, it seems. But that doesn't stop it breathing. The yard exhales that rich, fecund, just-past-summer breath of unloved back-of-building spaces I remember from the years when I lived on the lawless Lower East Side, back in the mid-eighties. K and I both lived there then, though we didn't know each other.

Sometime in the mid-eighties I lived in a squat for a few years-- an "urban homestead"-- on 13th and B. The building had been named:"Lucky Thirteen." We-- the whole displaced, conflicted association of us: anarchists, artists, losers, lost souls, "anti-capitalist" speculators and neurasthenic, grunge, gen-x-ers -- were working with our scavenged materials and tools to bring the building "up to code." Hah! how far from that we were, for every step toward it, we took three back, at least -- believing we stood a chance of possessing the building legitimately one day. We were waiting for the city to give up and turn the lease over to us. But instead they bulldozed the lot right out from under us.

"Lucky Thirteen"-- View from Back Window (1986) Miranda Field

"I mean," K continues, "we own this house. How lucky is that? I will never be homeless."